Confederate Naval Yards & Stations

By

Gary McQuarrie, Managing Editor

Neil P. Chatelain

OVERVIEW

When the Civil War started, the Confederate states did not have the facilities needed to construct or equip warships.1 The first centers of shipbuilding in the Confederacy were coastal cities that were also significant shipping ports–Norfolk, Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, and New Orleans. Eventually, shipbuilding facilities of various sizes and abilities were spread across many locations on the coasts and rivers of the South. Navy yards are significant facilities where ships can be dry-docked for repairs and extensive alterations, in addition to new construction. Naval stations are facilities where ships can undergo minor repairs and be supplied with fuel and necessary stores.2 When Virginia and Florida seceded, the Confederates captured two of the United States’ navy yards, Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard, Virginia and Warrington Navy Yard, Pensacola, Florida.3 When the Confederate States Navy was organized, it did not include a specific bureau to oversee construction, so shipbuilding efforts were widespread and poorly coordinated.

During the war, the Confederates had as many as dozen or so major naval yards and stations—these were bound by specified geographical boundaries as prescribed by the Secretary of the Confederate States Navy, Stephen Mallory—the station commander typically oversaw recruiting, storehouses, hospitals, marine detachments, ordnance works, and naval construction and received all local requisitions, handling administrative matters and inspecting commissioned vessels in port—they did not have operational control over navy squadrons unless so instructed by the secretary. After the principal Southern ports were captured by Union forces, naval yards and stations were located in the interior geographically for defensive purposes. The principal naval yards and stations of the Confederacy are summarized below, organized by state, along with some key facts and some additional documentary sources.1-4 The summary is not intended to be a comprehensive list of the all of the shipbuilding facilities, yards, and locations in the South during the war. A separate list of Confederate shipbuilding locations is available under Resources.

References

1. William N. Still, Jr. Facilities for the Construction of War Vessels in the Confederacy. The Journal of Southern History, Volume XXXI, No. 3, August 1965, p 285-304.

2. Margaret E. Wagner, Gary W. Gallagher, and Paul Finkelman, Editors. The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2002), p 543, 545-547.

3. William N. Still, Jr., Editor. The Confederate Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861-65 (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1997), p 21-39, 69-90.

4. John H. Eicher and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001), p 87.

VIRGINIA

Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard

The Gosport Navy Yard located in Portsmouth, across the Elizabeth River from the larger city of Norfolk, was abandoned by the Union, with many vessels set afire and scuttled, and captured by the Confederates on April 20, 1861. At the time, it was one of the finest navy yards of the United States and had the oldest continuously operating dry dock in the country. Its capture resulted in almost 1,100 heavy guns and a large amount of war material. The hull of the burned-out USS Merrimack was used to construct the CSS Virginia, the Confederates’ first ironclad. Gosport was also a naval ordnance facility while the Confederates held it. In May 1862, the Confederates burned the navy yard when they were forced to leave it and it was reoccupied by Union forces; after this, the “Gosport” name was dropped and it was renamed Norfolk Navy Yard to avoid confusion with the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, Maine.

Commanders

—French Forrest, April 22, 1861-1862

—Sidney S. Lee, March 27, 1862-May 1862

Additional Information

John V. Quarstein. The Capture of Gosport Navy Yard. Civil War Navy—The Magazine, Volume 5, No. 4, Spring 2018, p 13-23.

Alan B. Flanders. The Night They Burned the Yard. Civil War Times Illustrated, Volume XVIII, No. 10, February 1980, p 30-39.

Richmond Navy Yard (Rocketts)

Besides the Confederacy’s capital, Richmond was a seaport on the James River and a natural location as a significant naval center. Before the spring of 1862, the waterfront at Rocketts was the site of a limited shipyard operation. After launching at Gosport, the ironclad CSS Richmond was completed at this yard. The ironclad Fredericksburg was also built at this site, as was the unfinished CSS Texas. In the spring of 1862, a second shipyard directly across the James River from Rocketts, adjacent to the city of Manchester, was established—the ironclad Virginia II and several torpedo boats were built at this site, as was a naval hospital. Richmond also became a significant naval ordnance facility and had its own naval hospital and naval pharmaceutical laboratory. From mid-1863, Richmond supplied itself and Wilmington, North Carolina with naval ordnance material. Richmond served as the naval station for the James River Squadron.

Commanders

—Ebenezer Farrand, 1862

—Robert Gilchrist Robb, 1862-1865

Additional Information

John M. Coski. Capital Navy (New York, NY: Savas Beatie, LLC, 1996).

NORTH CAROLINA

Charlotte Navy Yard

Established in May 1862, Charlotte Navy Yard replaced the lost yard at Gosport. Charlotte was chosen for its rail connections with coastal cities. Nearly all propellers, shafts, and anchors for the Confederate Navy were manufactured here, as well as many parts for steam power plants on vessels. Various workshops, machinery, and tools were transferred here from Gosport. It was also a navy ordnance facility, and produced gun carriages, wrought-iron shot, and other ordnance stores. From mid-1863, Charlotte supplied ordnance material to itself, Savannah, and Charleston. The yard remained in operation until the final flight of the Confederate Government in April 1865.

Commanders

—Samuel Barron

—Richard L. Page, October 1862-1864

—Henry A. Ramsay, 1864

—George N. Hollins

—Catesby ap R. Jones

Additional Information

Violet G. Alexander. The Confederate States Naval Yard at Charlotte, N.C. 1862-1865. Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume XL (New Series, No. II), September 1915, p 183-194.

Ralph W. Donnelly. The Charlotte, North Carolina, Navy Yard, C.S.N. Civil War History, Volume 5, No. 1, March 1959, p 72-79.

Wilmington

Located 20 miles upstream from the mouth of the Cape Fear River, Wilmington became the most important and accessible port for blockade runners during the war. While Wilmington was not known for its shipbuilding, the Richmond-class ironclads CSS Raleigh and CSS North Carolina were constructed in two private yards, one of which, Beery’s shipyard, would have another under ironclad construction at the end of the war, CSS Wilmington—this shipyard was commonly referred to as the ‘Navy Yard.’ Wilmington had one of the most modern iron foundries in the state, and many machinery parts and heavy propeller shafts could be produced locally. The Wilmington Naval Squadron, which never amounted to a significant naval force, was under command of Flag-Officer Captain William F. Lynch, with its station at Wilmington. Its primary purpose was to defend the inland waters in case the Union Navy was able to force its way upriver. From mid-1863, Richmond, Virginia supplied naval ordnance material to Wilmington. When Fort Fisher fell to the Union forces on January 15, 1865, the final Confederate port city was soon to be captured. When the city was evacuated on February 22, 1865, CSS Wilmington was set afire.

Commanders

—William T. Muse, 1861-April 8, 1864

—James W. Cooke, 1864-1865

SOUTH CAROLINA

Charleston

An important coastal town and shipping port, Charleston’s existing shipbuilding facilities made it an obvious choice as a location to construct or convert vessels to warships. The wharfs and shipbuilding yards served as a base for the squadron of gunboats and ironclads developed in the harbor, including CSS Palmetto State, CSS Chicora, CSS Columbia, and CSS Charleston, the latter serving as the flagship of the Charleston Squadron. From mid-1863, Charleston possessed a naval hospital and was supplied with ordnance material from Charlotte, North Carolina. Charleston was also the site of construction of a number of torpedo boats and for the manufacturing and deployment of various types of torpedoes, as well as the home port of the submarine H.L. Hunley.

Commanders

—Henry J. Hartstene, 1861

—Duncan N. Ingraham, 1862-1865

Addition Information

Ron Field. Charleston Naval Station, 1861-1865, Civil War Navy—The Magazine, Volume 8, Issue 1, Summer 2020, p 50-57.

GEORGIA

Columbus

Situated far up the Chattahoochee River, which feeds into Apalachicola Bay, Florida, the Confederate Navy’s iron works in Columbus was among the most effective in the South. Taking possession of the Columbus Iron Works in 1862, the navy quickly expanded its operations. Machinery shops were quickly adapted and expanded to include a rolling mill and boiler plant. These provided iron plating, engines, boilers, and other engineering machinery for ships across the Confederacy, particularly those in Mobile, Savanah, and Charleston. Furthermore, the iron works also produced at least 80 naval cannon and gun carriages of various sizes. A shipyard near the iron works worked fervently and completed the ironclad ram CSS Jackson (originally Muscogee) in late 1864 but had in complete armor plating. Union forces assaulted Columbus on April 16, 1865, capturing the city, the ironworks, and the navy yard. The next day, the ironclad CSS Jackson was cut loose and set afire to drift downriver where it sank, and the yard was burned. The nearby damaged gunboat CSS Chattahoochee (which had been constructed at Saffold, Georgia) was also burned by retreating Confederates to prevent its capture.

Commanders

—James H. Warner, Naval Iron Works, 1862-1865

—Augustus McLaughlin, Naval Shipyard, 1862-1865

Additional Information

Raimondo Luraghi. A History of the Confederate Navy, Translated by Paolo E. Coletta. (Annapolis, MD, Naval Institute Press, 1996), p 45, 282, 289.

William N. Still, Jr. Confederate Shipbuilding (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1969), p 38-39.

Savannah

The Confederate Navy quickly recognized Savannah, Georgia as a critical post and established a naval squadron and yard facilities there. The yard was a major facilitator for blockade runners in the early parts of the war and civilian shipyards oversaw construction of several wooden gunboats and the ironclads CSS Atlanta, CSS Savannah, and the ironclad floating battery CSS Georgia. Supporting the Savannah Squadron and the civilian shipyard of Henry F. Willink was a navy hospital. Coal and ordnance were supplied from Charlotte, North Carolina, while the navy’s facilities in Columbus, Georgia, provided major machine shops. When General William T. Sherman assaulted Savanah in December 1864, the squadron was burned and/or scuttled, the navy yard evacuated and supplies transferred, shipyards burned, and the incomplete ironclad CSS Milledgeville set afire. Sailors made their way either to join the naval squadron at Charleston, South Carolina or the navy works at Augusta, Georgia.

Commanders

—Josiah Tattnall, 1861

—Thomas W. Brent, 1862-1863

—Josiah Tattnall, 1862-1865

Additional Information

Raimondo Luraghi. A History of the Confederate Navy, Translated by Paolo E. Coletta. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996), p 30, 332.

Maurice Melton. The Best Station of Them All: The Savannah Squadron 1861-1865 (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2012), p 66, 151, 206, 388-389.

FLORIDA

Warrington Navy Yard, Pensacola

First established in 1825, it was the ninth navy yard established in the United States and the only one on the Gulf of Mexico at the time. By 1850, a dry dock had been established. Following Florida’s secession, the yard was surrendered to the Confederates on January 12, 1861, who occupied it from 1861-1862; when they left in May 1862, they burned much of what remained standing and Union forces reoccupied the yard.

Commanders

—Victor M. Randolph, January 12, 1861-

—Duncan N. Ingraham, 1861

—Thomas W. Brent, 1861-1862

ALABAMA

Mobile

The Confederacy operated significant naval facilities in Mobile, Alabama, all supporting the Mobile Squadron. Shipyards in Mobile constructed the wooden gunboats CSS Gaines and CSS Morgan and helped complete ironclads whose hulls were fabricated at Selma or Montgomery, Alabama, most notably the ironclad CSS Tennessee II, but also the ironclads or ironclad floating batteries CSS Huntsville, CSS Tuscaloosa, CSS Nashville, and CSS Phoenix. A naval hospital was organized to support the squadron and the city. Experimental submersibles and substantial use of torpedoes added to Mobile Bay’s defenses. Besides the Selma shipyards, Mobile was directly supported by the ordnance facilities in Atlanta, and the navy yard at Columbus, Georgia, which supplied engineering machinery. Mobile Bay was sealed in August 1864 and on April 12, 1865, the city surrendered, with its naval stores. The Mobile Squadron scuttled itself and sailors retreated, being paroled in May 1865 at Nana Hubba Bluff, Alabama.

Commanders

—Franklin Buchannan, 1863-1864

—Ebenezer Farrand, 1864-1865

Additional Information

Arthur W. Bergeron Jr. Confederate Mobile (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1991), p 70, 190-192.

Selma

Selma was strategically located on the Alabama River and had rich resources nearby. Selma was also home to a naval gun foundry and ordnance works, producing some of the finest naval guns available. Most of the ordnance cast at Selma supplied the navy and army at Mobile. The facilities here also supplied all of the navy’s wants for shells and artillery ammunition. At the shipyard near the gun foundry, the casemated ironclads CSS Huntsville and CSS Tuscaloosa were laid down in the summer of 1862 and sent downriver to Mobile in February 1863 to be armed, armored, and fitted out—neither would be completely finished. CSS Tennessee II was constructed and also towed downriver to Mobile, where she was armored and armed and commissioned in February 1864—she became the flagship of the Mobile Bay flotilla. CSS Memphis was apparently also built at Selma, but so seriously damaged on launching as to render her useless. Selma was also the location of a privately built submarine torpedo boat, Saint Patrick, which attacked USS Octarora unsuccessfully and was later scuttled. Selma was captured on April 2, 1865 and the foundry works destroyed.

Commanders

—Ebenezer Farrand, 1863

—Catesby ap R. Jones, 1863-1865

Additional Information

William E. Lockridge. Selma and the Confederate Navy. Civil War Navy—The Magazine, Volume 6, Issue 3, Winter 2019, p 27-37.

Maurice Melton. The Selma Naval Ordnance Works. Civil War Times Illustrated, Volume XIV, No. 8, December 1975, p 18-31.

William N. Still, Jr. Selma and the Confederate States Navy, Alabama Review, Volume 15, No. 1, January 1962, p 19-37.

MISSISSIPPI

Yazoo City

The Yazoo City Navy Yard emerged following the collapse and fall of both New Orleans and Memphis, as Confederate naval forces retreated up the Yazoo River. Commander Isaac N. Brown collected mechanics, machinists, and slave labor from across Mississippi to reconstitute a yard at Yazoo City to complete the ironclad CSS Arkansas in the summer of 1862. After that, Brown saw to establishing a more formalized navy yard complete with saw mills, machine shops, carpentry shops, and blacksmiths. In 1863, Thomas Weldon oversaw projects related to three ironclads undergoing construction or conversion there—none were completed, however, and the Yazoo City Navy Yard was burned on May 20, 1863, with all of its stores, supplies, and construction projects, as Rear-Admiral David D. Porter’s squadron approached.

Commanders

—Isaac N. Brown

Additional Information

Alexander Miller Diary, May 21, 1863. Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA.

Additonal report of Acting Rear-Admiral Porter, U.S. Navy, transmitting report of Lieutennt-Commander John G. Walker, U.S. Navy, commanding U.S.S. Baron De Kalb, Mouth Yazoo River, May 23, 1863. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I, Volume 25: Naval Forces on Western Waters (May 18, 1863 to February 29, 1864), p 7-9 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912).

“Payment Summary for Yazoo City, 1862-1863,” Subject File for the Confederate States Navy, 1861-1865. (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1091, Records Group 45, National Archives Building, Washington D.C.), Subject File PI: Industrial Activity.

LOUISIANA

New Orleans

Naval facilities at New Orleans were very decentralized, thanks to the numerous civilian shipyards operating there when the war began. Nonetheless, naval facilities were created to augment civilian establishments. The John Hughes shipyard in Algiers, Louisiana, converted dozens of river steamers for Confederate use and the ironclads CSS Louisiana and CSS Mississippi were constructed at the private yards owned by E.C. Murray and the brothers Asa and Nelson Tift, respectively, both in Jefferson City, Louisiana. Civilian iron works were also employed to manufacture artillery. To augment these, naval commanders established a hospital and receiving ship (CSS St. Philip), and a naval laboratory to manufacture ordnance and shipboard material, and ammunition. The shipyards and facilities fell into Union hands when New Orleans was captured in April 1862, while the incomplete ironclads were destroyed to prevent their capture.

Commanders

—Lawrence Rousseau, March 1861

—George N. Hollins, August 1861

—William C. Whittle, March 29, 1862-April 25, 1862

Additional Information

Treasury Department Receipt, June 26, 1863, Leeds and Company Papers (National Archives Microfilm Publication M346, Record Group 109), National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series II, Volume 1, Part 4: Investigation of Navy Department, p 777 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921).

Chester G. Hearn, The Capture of New Orleans 1862. (Baton Rouge, LA, Louisiana State University Press, 1995), p 77-78, 141.

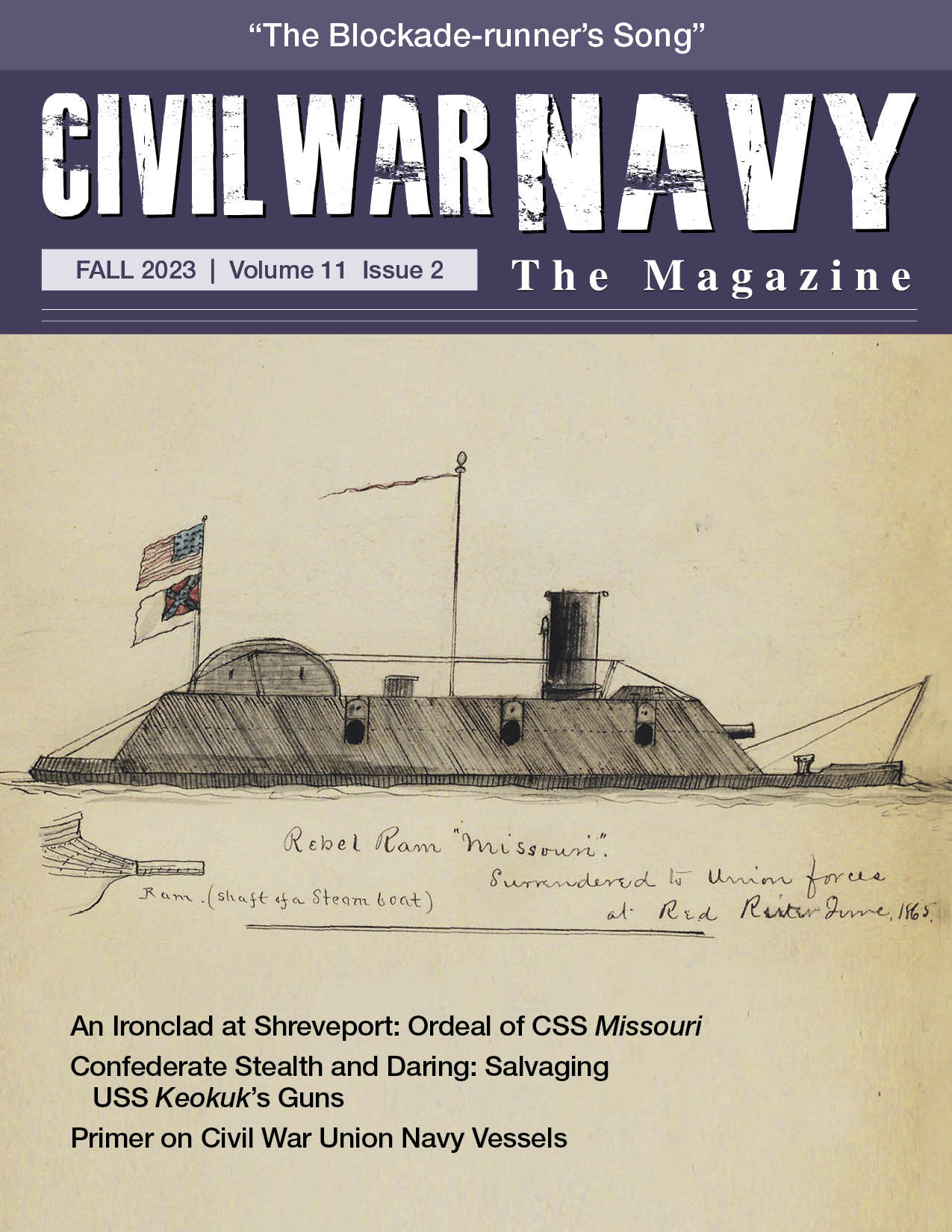

Shreveport

Established in 1862 after the Union capture of New Orleans, the navy yard at Shreveport constructed the ironclad CSS Missouri and several torpedo boats that were never employed in battle. Besides this, it outfitted, repaired, and supplied several Confederate naval and army warships, including CSS W.H. Webb, and army vessels Mary T, and Grand Duke. First Lieutenant Jonathan H. Carter surrendered the yard on June 3, 1865, along with the ironclad CSS Missouri and several army transports, with Union forces occupying it on June 7.

Commanders

—Jonathan H. Carter

Additional Information

Katherine Brash Jeter, Editor. A Man and His Boat: The Civil War Career and Correspondence of Lieutenant Jonathan H. Carter, CSN (Lafayette, LA: University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1996), p 70, 74.

Report of Lieutenant-Commander Fitzhugh, U.S. Navy, regarding the receiving of surrender of men and material of C.S. Navy, in Red River, U.S.S. Ouachita, Alexandria, La., June 3, 1865, to Acting Rear-Admiral S.P. Lee, commanding Mississwippi Squadron. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series 1, Volume 27: Naval Forces on Western Waters (January 1 to September 6, 1865), p 229-231 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1917); Report of Lieutenant-Commander W.E. Fitzhugh, U.S. Navy, U.S.S. Ouachita, Mound City, June 20, 1865, to Acting Rear-Admiral S.P. Lee, Commanding Mississippi Squadron, regarding surrender of Confederate naval property in Red River. Ibid, p 238-239.

TENNESSEE

Memphis

An inland navy yard was first proposed by Mathew Fontaine Maury, and in 1843, the city was examined as a potential host of a shipyard. Construction of this navy yard began in 1845 but was never completed. Facilities there did expand, however, and the Pittsburgh-constructed warship Alleghany spent three months outfitting at the Memphis Navy Yard in 1847. In 1854, the yard was closed, with its land returned to the city of Memphis. Upon secession, civilian John T. Shirley operated a yard at Memphis for ironclad construction, including the never-completed ironclad CSS Tennessee and the ironclad CSS Arkansas that was completed on the Yazoo River. The Memphis Navy Yard never finished any ships by the time the city fell to Union forces in June 1862.

Commanders

—John T. Shirley

Additional Information

Walter Chandler. The Memphis Navy Yard, An Adventure in Internal Improvement, West Tennessee Historical Society Papers, Volume I, 1947, p 68-72.

William N. Still, Jr. Confederate Shipbuilding (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1969), p 29.